The Project

Clip from Cley Marshes: A Wild Vision, a film produced by David North for the Norfolk Wildlife Trust’s Cley Marshes Appeal, Catherine Mason & John Hurst speaking about the history of landscape painting in the region

Holme-next-the-Sea, photographed by the author. Beaches in Norfolk have been called “the front line against the sea” (Simon Harrap:2008). Tough perennial grasses Sand Couch and Marram are key plants in the formation of dunes.

History

In terms of landscape North Norfolk has a unique character due to the conurbation of land and the North Sea. It is dominated by the nebulous coast, in some parts it is a land reclaimed from the sea. It is this liminal quality which marks it out – being at the edge of where the land meets the sea, a threshold of constantly changing proportions. North Norfolk is not a place en route, it is the destination. (As a local saying has it “Norfolk is cut off on three sides by the sea and on the fourth by British Rail.”)

Three-quarters of the coast of North Norfolk is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, with many Sites of Special Scientific Interest and England’s largest designated National Nature reserve of 10,000 acres in the nine miles between Burnham Overy and Blakeney. The natural landscape is characterised by sweeping open beach and sea vistas, natural harbours, fresh and salt marshes, tidal creeks, mud flats, reedbeds, heathland, green pastures and those famous big skies, all watched over by the weather.

There are few places in England where you can get so much wildness and desolation of sea and sand-hills, wood, green marsh and grey saltings as at Wells, in Norfolk, the small old red-brick town, a mile and a quarter from the beach, with a green embankment lying across the intervening marsh connecting town and sea.

A short excerpt from Adventures Among Birds, by William Henry Hudson published 1913 and re-printed in Knowing Your Place, page 144. Hudson, born 1841, settled in England in 1874 from Buenos Aires (his birthplace). His early writings helped foster the back-to-nature movement of the 1920s and 30s and he was a founder member of the RSPB.

This is the home or temporary stopping-off place for thousands of birds, seals and wildlife. Due to its geographical positioning and habitat the county of Norfolk has been called the “bird capital of Britain” (Neil Glenn, Best Birdwatching sites in Norfolk, 2006). The bulky land-mass of East Anglia that juts out into the North Sea points towards Europe and Scandinavia providing a landfall for migrating birds. To the left is the Wash, a huge estuary of mud abundant in invertebrates, a crucial food for wintering wading birds. Salt marsh is internationally important for many breeding species and over-wintering wildfowl. Up to a third of the world’s population of Pink-footed Geese spend the winter on these marshes. With similar marshes in Essex and Kent becoming concreted-over, the Norfolk marshes have become even more crucial to the ecosystem.

The largest colony of seals in Britain is to be found at Blakeney Point, with around 500 resident grey and common seals.

In Britain generally most of the landscape we see around us tends to be filtered, constructed, a product of centuries of change depending on how it has been managed and manipulated by generations of human intervention and weather conditions. North Norfolk’s ‘Salt marsh Coast’ is unique and one of the last surviving areas of true wilderness in the country.

Saltmarsh near Stiffkey photographed by the author. Saltmarsh is formed very slowly over thousands of years by deposits of fine sediment in locations where the coast is sheltered by spits and sandbars. This allows the silt to settle to the bottom, trapped in place by plants which prevent it from being washed away. The whole area is dominated by tides which vary in height thus providing a unique range of conditions for flora and fauna to thrive. In Norfolk, parts of the 2,000 hectares of saltmarsh (which stretches from Holme to Salthouse) was formed 6,000 years ago. This coastline is often known as the Saltmarsh Coast and is an internationally important site for many breeding species of birds and over-wintering wildfowl. Most of the saltmarsh in Norfolk is largely unspoilt, having been protected (for the most part) from development and therefore has huge importance as one of the last areas of true wilderness in Britain.

Of course, in common with other areas of countryside in England, here too there is a juxtaposition of the wild with the man-made.

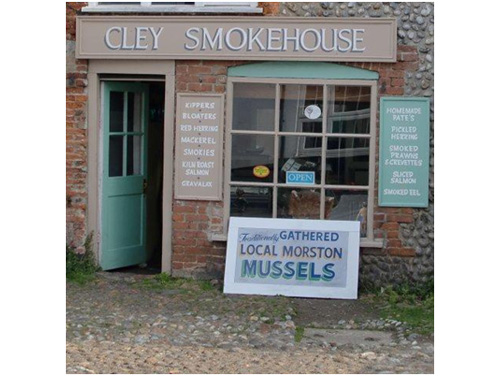

The man-made landscape is characterised by working ports, agricultural fields, livestock, windmills, historic villages, pebble and flint-walled cottages, church towers, sea defences, wind farms, among other things.

“What would you be, you wide East Anglian sky,

Without church towers to recognise you by?

What centuries of faith, in flint and stone,

Wait in this watery landscape all alone.”

The first four lines of a poem by John Betjeman. Norfolk has the highest concentration of medieval churches in the world and is especially known for its hammer-beam roofs decorated with carved angels. My favourite is the Church of Our Lady, St Mary South Creake. Believed to be built 1415, the angels were restored in the 20th-Century. Fakenham Parish Church & St Mary Sandringham also has beautiful carved roof angels.

Today the land is used by people both as a source of livelihood and for recreation purposes. Some of these include farming, fishing, gathering, tourism, retirement, and a wide variety of popular leisure pursuits such as walking, horse riding, birdwatching, shooting, sailing and fishing. It is also subject matter and inspriation for numerous professional artists. Many of these are inter-dependent. Where such variety of work and leisure activities co-exist and jostle for place, there is on-going debate as to what constitutes appropriate use of natural and human resources.

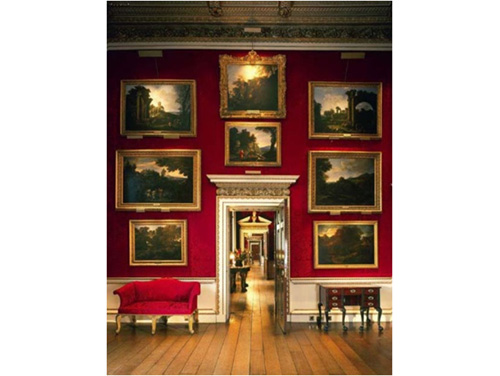

Britain has a rich and diverse landscape and among the peoples of this nation there has long been a love affair with the land and the countryside. It follows that within British art there is a grand tradition of landscape painting. So it may come as a surprise to learn that landscape as a genre in this Country derives from Continental painters. Prior to the 18th-Century with painters such as Lambert and Gainsborough (who mark the beginning of our modern idea of the countryside), the landscape of Britain was ignored by British artists and patrons. Although Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens in 1629 on a diplomatic mission to London commented on how beautiful this country was, early British landscapes only appeared as a backdrop, for example in Royal portraiture. It was the aristocrats, such as Thomas Coke 1st Earl of Leicester at Holkham Hall, bringing back classical landscape pictures from the European Grand Tour with which to furnish their houses that eventually sparked a taste for such subjects here.

The landscape gallery of Holkham Hall

Landscape architects William Kent, Capability Brown and others (most of who were trained painters), were hired to shape parklands around stately homes to create picturesque views inspired by European artists such as Claude Lorrain. In the early 1800s Norwich School watercolourists such as John Crome and John Sell Cotman took inspiration from Dutch painters including Jacob Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema who painted the landscape as a subject in its own right. (For more on the history of landscape see the page Aspects of Place in Art History.)

Although the landscape idiom appeared to be somewhat suppressed by the latter 20th-Century, as exemplified by the rise of Postmodernism and Brit-art, there do exist artists who remain interested in exploring aspects of place and find that landscape is still a vital genre within which to do this.

See a reading list here

In 2018 I curated the exhibition CONNECTION : OPEN 2018 – Celebrating the best East Anglian art to launch Wells Maltings Art Space

CONNECTION was the inaugural exhibition in the Handa Gallery and celebrated the quality and diversity of art in East Anglia today.

A call to artists with connections to East Anglia was made in October 2017, via an anonymous entry process. We were thrilled by the enthusiastic response, indicative of the large amount of talent in this region. A wide variety of styles, materials, methods and subject matter was immediately apparent as was the high standard of works submitted. From over 900 entries around 250 mostly two-dimensional works of art were selected. Painting, printmaking, mixed-media and wall-hung textiles, ceramics, mosaics and sculpture.

The idea was based on a true Open, taking inspiration from the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, giving visitors an opportunity to view and purchase work by artists at every level of their career, from emerging talent to established figures.

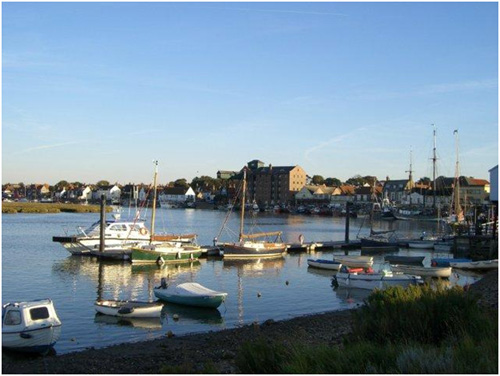

It showcased the new art space within the newly renovated landmark Maltings buildings on Staithe Street, Wells-next-the-Sea.

Prizes were awarded, with the First Prize of £500 going to Norwich-based Elizabeth Monahan, for her painting Blue, 2017.

Pictures of the show are here.

Selectors & Organisers:

Catherine Mason, art historian and author

Veronica Sekules, Groundworks Gallery, Kings Lynn

Tracey Ross, Artist and Art Tutor and Simon Daykin, Director of Wells Maltings

Text and images on this site are subject to copyright and may not be reproduced without permission.